From Big Ovens to Bento Boxes: Cooking Culture Shock in Japan

When I moved back to Japan, I missed many things from the U.S. — the wildlife around my house, the simplicity of trash disposal, and most of all, the smell of a backyard BBQ. But one of the biggest cultural shocks hit me right in the kitchen.

Every country has its own cooking customs, tools, and daily food habits. So if you're relocating to Japan, here’s what to expect — the good, the not-so-good, and a few tips to help you navigate it all.

I've added a “Cooking Conversion Cheat Sheet” to the Freebie Shelf — feel free to grab it!

In this blog;

1. No Room for a Big Oven or Grill

2. Different Cooking Styles = Different Habits

3. Tools & Space: What You Can’t Keep in a Japanese Kitchen

4. Cakes: Big, Bold vs. Small and Subtle

5. Lunch Box Culture: Not Just a Meal — A Message

6. The Basement Wonderland: Depachika Culture

7. Measurement Conversions That Saved Us

8. Adapting Without Losing Your Style

9. Wrap up

————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

1. No Room for a Big Oven or Grill

In the U.S., it’s common to roast a whole chicken, bake a lasagna, or slow-cook a brisket in a large oven. Many homes also have backyard grills for burgers and BBQ — it’s practically an all-season practice, not just for summer.

But in Japan, most apartments don’t even come with a proper oven. You’ll usually find a compact fish grill tucked under the stovetop (called a sakana guriru) and maybe a small microwave-convection combo.

If you visit appliance stores like Yamada Denki, Bic Camera, or Nojima, you can find full-size ovens — though not many. But fitting one into a Japanese kitchen isn’t easy. We seriously considered installing a gas oven and even looked into various models, but in the end, we gave up.

It was hard to find one that matched both the kitchen layout and our needs, and the cost was steep — around ¥600,000 + installation.

On top of that, we would have needed to get approval from the building management to ensure it didn’t violate fire safety rules or require changes to the ventilation system.

Gas ovens are uncommon in Japan, especially in apartments, and the installation process can be complicated. Between the lack of space, fire safety regulations, and limited support for gas appliances, it just wasn’t worth the effort for us. So, no big turkey roasting for Thanksgiving.

As for outdoor grilling, it’s rarely allowed in apartment complexes due to fire safety rules and smoke concerns. That said, we recently spotted a Weber grill at a local home center — and we’re seriously thinking of getting it for our parents’ countryside house, where space and smoke aren't an issue.

One more thing about grilling: the meat. In the U.S., we loved buying big, marinated skirt steaks. But in Japan, that cut is hard to find — and even if you do, it’s rarely pre-marinated and usually much smaller.

If you go to a Korean BBQ place in Japan, you can find a small cut called Harami. Harami refers to the skirt steak, specifically the outside skirt, located near the diaphragm. It’s known for its rich flavor and chewy texture.

Unlike more common cuts like ribeye or sirloin, Harami is considered offal (hormonei) in Japan, which is why it's often served at yakiniku or Korean BBQ restaurants rather than sold at regular supermarkets.

So, no Sunday roasts or smoky ribs here in the city. My husband once dreamed of bringing his beloved Weber grill to Japan. But unless you live in a house with a yard — it’s mostly a dream.

2. Different Cooking Styles = Different Habits

Once, I attended a team-building cooking event in the U.S. with the entire HR team — about 25 people — and several of them didn’t even want to use a kitchen knife. That would never happen in Japan.

Japanese — or more broadly, Asian — home cooking is very hands-on. It’s all about washing, peeling, chopping, boiling, simmering, sautéing, and plating. You use a wide variety of ingredients: vegetables, meats, fish, tofu, sauces, rice, noodles and spices. When you're working and raising kids, cooking can start to feel like just one more thing to get through. When it became a chore, I couldn’t enjoy it anymore. I’ve never been a great cook — though I do love eating!

In contrast, American home cooking tends to prioritize simplicity, volume, and convenience: think one-pot chili, sheet-pan dinners, or casseroles. Salads often come pre-washed in a bag. Proteins go straight into the oven or onto the grill.

It’s not better or worse — just different. Japan values seasonality, freshness, and visual. The U.S. leans more toward efficiency, bold flavors, and generous portions. And honestly, I’ve come to appreciate the efficiency of American-style cooking!

In Japan, there’s a saying: “Ichi-ju Issai” (一汁一菜) — meaning “one soup, one dish.” It refers to a simple yet balanced meal of rice, miso soup, and one side dish. Even a “frugal” meal still involves preparing three separate items. And if you go to a Korean restaurant, even a basic meal comes with 7–8 small side dishes. That’s a lot of prep! In the U.S., one big dish often covers everything — efficient and practical.

Healthy Cooking

From a health perspective, Japanese meals are typically lighter and more plant-based. Fish is much more common, and red meat is used sparingly. In the U.S., beef and chicken tend to dominate the dinner table. My husband actually lost weight after we moved to Japan — mostly thanks to walking more and eating a more vegitables diet.

3. Tools & Space: What You Can’t Keep in a Japanese Kitchen

We once had every kitchen tool imaginable — a meat hammer, meat thermometer, orange peeler, cast iron skillet, grill tongs, electric smoker, yogurt maker, pasta maker, sausage maker and all kinds of baking tools.

But when we moved to Japan, we had to let most of it go. There just wasn’t enough space.

Japanese kitchens are compact. Often, there’s just one sink, two or three burners, and no pantry. You might get one drawer and a small cabinet. Forget storing a dozen spices or multiple large pots — there’s simply nowhere to put them.

And unlike American kitchens, which are designed for multiple people to cook side by side, Japanese kitchens are usually built for just one person at a time.

Even kitchens in houses are typically a bit larger — but not by much. And space is only part of the story. There are deeper cultural and design reasons behind the small size of many Japanese kitchens:

The kitchen is traditionally seen as the wife’s domain — designed for one person, not a couple or family.

It’s often tucked away, not a focal point of the home, partly to hide clutter. (No wonder it’s commonly placed on the north side of the house!)

In Japan, many homes are designed by men who have never done housework — which might explain why some kitchens feel impractical.

In the U.S., wives often have a strong say when choosing a home, and the kitchen plays a big role — even husbands care about the kitchen.

🔹Real Story: So in the morning, it’s me, my husband, and even our dog (Jager) all crammed into the small kitchen — and it’s too crowded. He’s giving Jager his daily medication and making toast, I’m making coffee and tea, and Jager’s food and water bowls are in the kitchen too. We’ve had to be super careful not to accidentally kick Jager’s little head — he likes to sit right in the middle of everything!

We really miss our spacious U.S. kitchen: a huge refrigerator, two full-size ovens, four stove tops, a long L-shaped countertop, a pantry, a spice shelf, and a dishwasher. We never bumped into each other — even when we were both cooking at the same time for family gatherings or special occasions.

4. Cakes: Big, Bold vs. Small and Subtle

Let’s talk about desserts. In the U.S., cakes are often bold and colorful — layered, frosted, sprinkled, sometimes even neon-bright. One slice can be huge, packed with sugar and buttercream. Think birthday cakes from Costco or a triple-chocolate fudge cake from a diner.

In Japan, cakes are a whole different story. They're delicate, light, and often beautifully minimal. A typical slice is modest in size and flavored with fresh fruit, whipped cream, or subtle ingredients like matcha or chestnut.

The sweetness is restrained — almost elegant. Japanese cakes are as much about texture and balance as they are about taste.

That said, for big celebrations, American cakes make a strong impression. They’re made for parties — grand, festive, and meant to be shared.

5. Lunch Box Culture: Not Just a Meal — A Message

In the U.S., a packed lunch often means a peanut butter sandwich, a bag of baby carrots, and maybe a cookie. Quick, practical, done.

In Japan, lunch boxes — especially for kids and working spouses — are on a whole other level. A typical bento includes rice, grilled fish or chicken, two or three vegetable sides, a tamagoyaki (rolled omelet), and maybe some fruit. Some moms even go the extra mile to make kyaraben — character-themed bentos shaped like pandas or anime faces.

Not me. I’m the clumsy type.

🔹 Real Story: My husband used to say that his expat colleagues from Japan always brought beautiful homemade lunches prepared by their wives — and he was so impressed by the lunch boxes.

I think he secretly hoped that when he married a Japanese woman, a beautiful bento would come with the deal. It didn’t.

He now says, “I want my money back.” Well... too late!

But beyond the food, bento is about more than nutrition — it shows care. It’s about presentation, thoughtfulness, and balance. In many ways, it's love packed in a box.

6. The Basement Wonderland: Depachika Culture

One of the most fascinating and delicious discoveries in Japan is the depachika — the basement food floor in major department stores like Isetan, Takashimaya, or Mitsukoshi. These are not average food courts. They are gourmet wonderlands packed with delicatessen counters, high-end bentos, sushi boxes, specialty pickles, hand-made sweets, and global cuisine.

In the U.S., you might find some prepared foods near the deli counter at Whole Foods or Costco — various hams, salads, maybe rotisserie chicken. But it’s nothing like the variety, quality, and elegance of a Japanese depachika.

You can pick up restaurant-quality meals without cooking a thing: grilled fish, tempura, simmered vegetables, or even Western-style dishes like croquettes and pastas. Whether you’re too tired to cook or just want to sample something new, depachika culture makes eating at home feel luxurious.

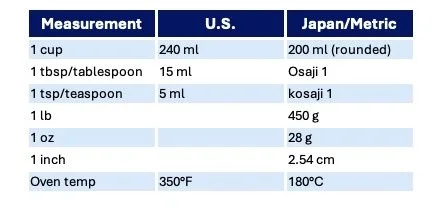

7. Measurement Conversions That Saved Us

Finally, a quick cheat sheet for anyone cooking across cultures. Japanese recipes use metric units, and kitchen scales are common. American recipes use cups, teaspoons, Fahrenheit, and “pinches.”

Here’s a quick conversion chart I use often:

*Osaji” and “kosaji” refer to Japanese measuring spoons— equivalent to a tablespoon and a teaspoon, respectively

🚨Tip: If you're following a Japanese recipe, get a kitchen scale. If you’re in Japan trying to follow U.S. recipes — double-check your oven or toaster settings, because not all Japanese appliances allow exact Fahrenheit-to-Celsius translation.

I've added a handy conversion chart in PDF format to the Freebie Shelf — feel free to print it out and stick it on your kitchen wall!

10. Adapting Without Losing Your Style

Moving to Japan doesn't mean you have to give up your cooking style — it just means adapting creatively. While I had to say goodbye to some of my favorite tools (goodbye, sausage maker!), I’ve found ways to merge American habits with Japanese realities.

Here’s what we’ve done:

a. Maximizing kitchen space with DIY solutions

Japanese kitchens often have poorly optimized storage — lots of dead space under the sink or stove. We added custom shelves to create a second layer in those areas, which doubled our storage capacity.

(We gave up trying to install an oven under the stovetop — the space just didn’t work.)

b. Finding the right ingredients

Yes, some ingredients are harder to find — but not impossible. Many spices and specialty items are available at import-friendly stores like National Azabu, Kinokuniya, and KALDI Coffee Farm. Some local supermarkets even have international sections if you know where to look. And when all else fails — there’s always Amazon.

c. Swapping ingredients and making things from scratch

We’ve learned to adapt recipes. For example, we use mozzarella instead of ricotta cheese (though you can find ricotta at KALDI). We also use komatsuna instead of kale. As for Buffalo chicken wing sauce — we couldn’t find the exact one, so we made it from scratch to get the perfect spice level.

d. Kitchen hacks

My husband taped the conversion cheat sheet inside a kitchen cabinet door. That way, he can still use the American cookbooks he brought from the U.S.

What matters most is staying connected to your own food story. You don’t have to make panda-shaped bentos. Start with what you know, then experiment slowly. The goal isn’t to become someone else — it’s to make Japan feel like home, one meal at a time.

11. Wrap-up

Like anywhere in the world, Japan has amazing local dishes to discover. I hope you’ll enjoy exploring Japanese cuisine and cooking — but also feel free to keep cooking what feels familiar and comforting.

Most ingredients are available if you know where to look — whether at import shops, specialty stores, or online.

Home cooking can be healthy (no strange chemicals added), budget-friendly, and even fun — as long as it doesn’t feel like a duty.

Food is joy. And good food makes good days !

Don’t forget to grab the Cooking Conversion Cheat Sheet in the Freebie shelf.