Buddhism in Japan: Quiet Traditions That Shape Unique Daily Life

When my American husband attended his Chicago high school reunion last week, he learned that a friend and her husband had become Buddhists. They were thrilled when he mentioned living in Japan.

“Oh, then people must go to temples!” they exclaimed.

The truth? Many Japanese don’t visit temples weekly, unlike Western Sunday services. Yet, we embrace Christmas with festive meals and gifts.

Despite this, Buddhism—and Shinto—remains quietly woven into daily life, shaping Japan’s calendar and community. In this article, I’ll guide you through how these traditions appear in everyday Japan.

This article covers:

1. Shinto and Buddhism in Plain Words

2. Seasonal & Community Moments

3. Life Events & Milestones

4. Personal & Everyday Encounters

5. Wrap up

1.Shinto and Buddhism in Plain Words

First, let’s briefly clarify what Shinto and Buddhism are.

Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion, is unique to the Japanese people, rooted in nature, the land, and countless kami (spirits or deities, 八百万の神). Shrines are where people pray for blessings, health, and prosperity, without a founder or scripture.

Tip: Shrines (jinja) are where people pray for blessings, health, and prosperity. Some shrines carry special titles, such as gu (宮) for historically important shrines (e.g., Nikko Toshogūu, Tsurugaoka Hachimangu), or taisha (大社) meaning “grand shrine.”

Buddhism arrived from India via China and Korea in the 6th century, bringing temples, statues, and teachings on impermanence and enlightenment.

This blending has evolved over centuries. Today, many Japanese pray at Shinto shrines, enjoy Christian-style weddings, and attend Buddhist funerals—all without contradiction.

Real story:

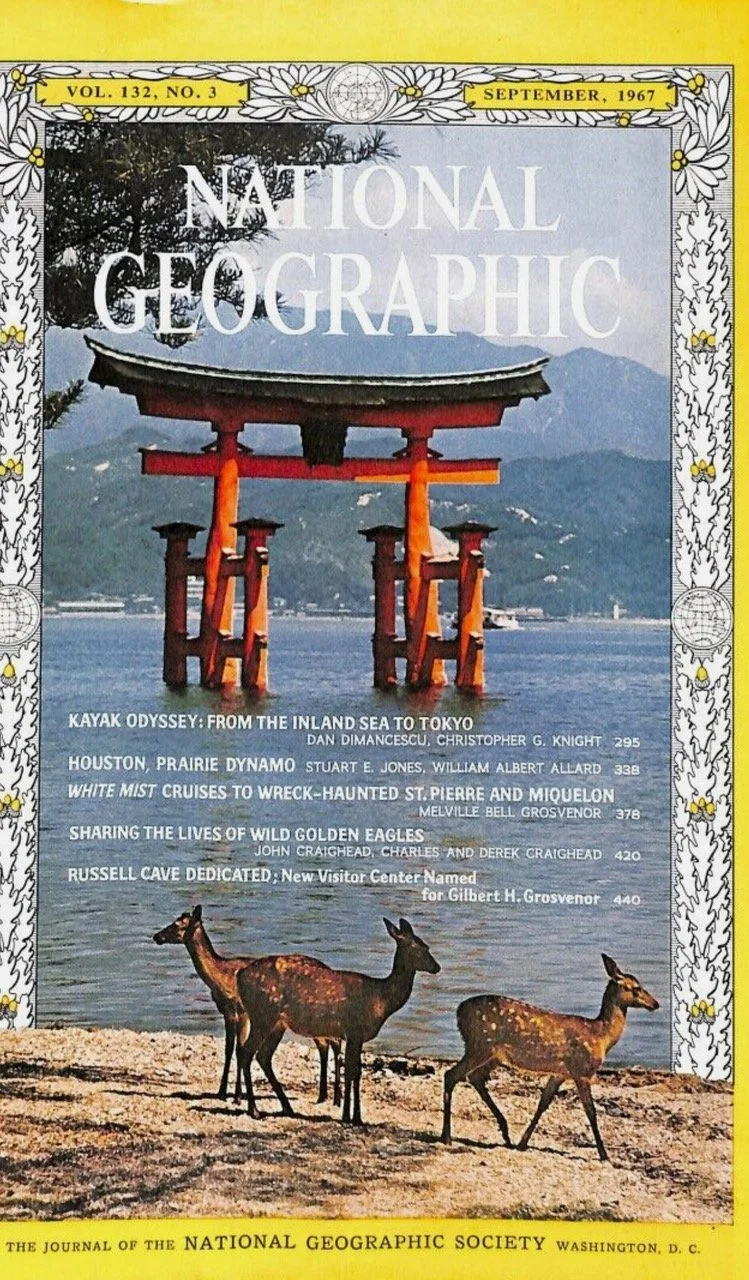

A 10-year-old American boy was enchanted by a National Geographic photo of Itsukushima Shinto Shrine in 1967. Fifty-seven years later, he retired to Japan. Dreams can take time, but they do come true.

2.Seasonal & Community Moments

Joya no Kane (除夜の鐘/New Year’s Eve Bell) – December 31

On the final night of the year, temples across Japan ring their bells 108 times at temples. This is called Joya no Kane, a ritual that symbolizes clearing away the 108 earthly desires that cause human suffering. Even on TV, people can hear the deep, solemn sound resonating into the midnight sky.

Real Story: A Life-Changing New Year's Eve in Japan

An Australian friend once told me he never really liked the loud New Year's Eve parties. Then, he spent New Year's Eve in Nara, Japan. It was completely silent—until midnight.

A deep temple gong echoed through the night—a sound of prayer.

At that moment, he knew. This was where he wanted to live.

Hatsumode (初詣/First Visit of the Year) – January 1–3

The first shrine or temple visit of the year, known as Hatsumode, draws millions of people across Japan. Some go to Shinto shrines, others to Buddhist temples — often both.

Families buy omamori (protective amulets), draw fortunes, and pray for good luck and peace. It’s less about religion and more about starting the year with hope.

What are omamori? The word literally means “protection,” and there are many types: for success in studies, love, business, recovery from illness, health, prosperity, safe driving, and more.

I always keep one in my purse.

Setsubun (節分)– February 3

This day marks the seasonal shift from winter to spring. At temples and shrines, people throw roasted soybeans while shouting “Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!” (“Demons out, fortune in!”).

Traditionally, the beans are thrown at imaginary demons (鬼) — or at someone dressed up as a demon, especially at nursery school events. Families used to do this at home as well, though it’s less common today.

It’s a mix of Shinto seasonal observance and Buddhist temple practice — another example of how traditions overlap in Japan.

My story: When I was a child, my father would shout “Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!” so loudly that everyone in the neighborhood could hear him. I was too shy to join in, but it remains a fond memory.

Another custom is eating ehomaki, a thick sushi roll eaten on Setsubun. Before I went to the U.S., this wasn’t common. But when I came back, it had become a new tradition. Times change, but this event continues.

O-higan(お彼岸) – Spring & Autumn Equinox

Twice a year, during the spring and autumn equinox, families make offerings at the household butsudan (Buddhist altar) — typically flowers, and in my region, foods like tempura or ohagi (sweet rice cakes with red bean paste). They also visit family graves to honor ancestors.

This practice is Buddhist in origin. It is based on the belief that the world of the living and the world of the dead are closest during these times of equal day and night.

Since the equinox is also a national holiday, many people take the opportunity to gather as a family, making O-higan both a spiritual and cultural tradition.

O-bon (お盆)– Mid-August

Perhaps the most famous Buddhist seasonal event, O-bon is when ancestral spirits are believed to return home. Families welcome them with lanterns, visit graves, and sometimes dance Bon Odori in temple courtyards.

Even if you don’t think of yourself as religious, O-bon is often a family reunion season, rooted in Buddhist ideas of remembrance.

O-matsuri(お祭り/Festivals)and Temple Events

Since ancient times in Japan, people have prayed to the deities of nature for a good harvest, good health, and safety. Over the centuries, these prayers became rituals and festivals, firmly rooted in daily life and passed down through generations.

Many o-matsuri are Shinto in origin, but Buddhist temples also play an important role in community life. These events are usually supported by local community members, and schedules are often posted on neighborhood bulletin boards.

While famous festivals like the Gion Festival in Kyoto or the Kanda Festival in Tokyo draw huge crowds, the smaller celebrations in local villages create memories that last a lifetime.

3.Life Events & Milestones

Wedding (結婚式/kekkon shiki)

Today, many Japanese couples choose Western-style weddings — often in a chapel setting with white dresses, tuxedos, and even a hired pastor. Still, Shinto-style and Buddhist-style wedding ceremonies continue to exist.

Shinto-style weddings: These follow a traditional form dating back to the Muromachi period. The couple reports their union to the kami (deities), expresses gratitude, and asks for blessings. The ritual emphasizes harmony with nature and respect for family heritage.

Buddhist-style weddings: Very rate today. They are based on the Buddhist teaching of innen (因縁, karmic connection) — the idea that marriage is not accidental, but the result of bonds formed in past lives and the compassion of ancestors. In the ceremony, the couple vows to carry this connection into the next life as well.

O-miya Mairi(お宮参り)

When a baby is born, the family takes the child to a Shinto shrine for a first visit called O-miya Mairi (also known as Hatsu-miya Mairi or Hatsu-miya Mode).

During this ceremony, the family reports the baby’s birth to the ujigami (氏神, the local guardian deity of the area) and prays for the child’s healthy growth and protection.

O-miya Mairi is considered one of the most important early milestones in a child’s life, connecting the newborn not only to the family but also to the community and its traditions.

Funerals (お葬式/O-soshiki)

In Japan, most funerals are Buddhist, even for families who rarely visit temples otherwise. The priest chants sutras, incense is offered, and mourners bow in respect. Buddhism is strongly tied to how Japanese people understand death and remembrance.

Memorial Days: 7th, 49th, and Anniversaries

After a funeral, families hold memorials on the 7th day, the 49th day, and later on the 1st, 3rd, 7th, 13th, and even 33rd anniversaries. These dates mark the soul’s journey in Buddhist tradition.

Even for non-devout families, these are cultural expectations — ways to gather, remember, and honor the deceased.

O-hakamairi (お墓参り/Grave Visits)

Beyond Obon and Ohigan, families often visit graves during anniversaries. They clean the gravestones, place flowers, light incense, and bow. It’s a quiet ritual, yet one of the most enduring ways Buddhism shapes everyday family life.

4.Personal & Everyday Encounters

Prayers for Help and Protection

When facing exams, illness, or travel, people often visit Shinto shrines. But Buddhist temples are also places to pray for peace, buy protective amulets, or light incense. The boundaries between the two traditions are fluid.

Real story

In Japan, there’s a saying: kurushii toki no kami-danomi (苦しい時の神頼み), which means “When in trouble, rely on the gods.” Even people who don’t consider themselves religious often go to a shrine or temple when faced with illness, difficulties, or uncertainty. We pray when we need help. Convenient, isn’t it?

O-Butsudan (お仏壇/Household Altars)

Many Japanese homes contain a butsudan, a small Buddhist altar to honor ancestors. Not every family uses it daily, but it’s a reminder of continuity between generations.

Danka (檀家): Japan’s Family–Temple Connection

In Japan, some families have a special relationship with a specific Buddhist temple, known as danka (檀家). A danka family supports the temple financially through offerings or donations, and in return the temple provides important services such as funerals, memorial rites, and grave maintenance.

The temple that a danka family belongs to is called their bodaiji (菩提寺). This bond often continues across generations, linking families to the same temple for centuries.

A brief history: The danka system began in the Edo period (around 1635), when families were required to join a temple for religious control and population monitoring, which also spread Buddhism.

Though later abolished, temples stayed central to community life. Today, local governments manage resident registration — a reminder of the role temples once played.

Wrap up: The Quiet Presence of Buddhism

I have never thought of myself as a Buddhist, yet Buddhist traditions have always lived quietly around me. In a countryside home, a large family altar stands as it has for generations. Each time I visit, I pause to pray — offering small wishes for health, safety, and peace.

I am also drawn to temples and shrines, especially those surrounded by beautiful gardens. Their history, architecture, and quiet teachings seem to enter the heart without effort. In their stillness, the world feels a bit lighter.

In the end, Buddhism in Japan is not loud or formal. It is a quiet presence, woven into daily life, waiting in the background for moments of reflection.

Have you experienced temples or shrines in Japan? I’d love to hear how they touched you — share your story in the comments!

See also: How to Navigate Inheritance, Wills, and Tax in Japan for Foreigners