Pain Control in Japan: Why So Little Medication, and What’s Changing

In the U.S., pain control is seen almost as a right. In Japan, it’s often the last resort. That single line captures the cultural and medical gap I’ve experienced firsthand—first while living in the U.S., and later upon returning to Japan.

For many Americans, pain control is an integral part of healthcare. Hospitals and clinics treat pain aggressively, with doctors often prescribing strong medications after surgeries, injuries, or even dental work. The logic is simple: comfort equals good care.

In Japan, the philosophy is very different. Pain control is available, but it is approached with caution, and usually delivered with far milder options.

This blog is not medical advice, but a cultural and systemic comparison: why Japan’s approach to pain control is so different, how it feels as an expat, and what you should know to prepare yourself if you ever need care here.

Disclaimer: I am not a medical professional. This article is based on my experiences and research, and is for general information only — not medical advice.

This blog covers:

1. The U.S. Approach – Comfort First

2. The Japanese Approach – Caution and Low Doses

3. Numbers Tell the Story

4. What Expats Should Know (Practical Tips)

5. Steps Toward Better Pain Control

6. FAQ

7. Warp up

1.The U.S. Approach – Comfort First

In the U.S., pain isn’t just a symptom—it’s treated like a vital sign, as important as your heartbeat or blood pressure.

Hospitals often ask, “How bad is your pain on a scale of 1 to 10?” right alongside checking your blood pressure or running blood tests.

Americans expect a hospital visit to not only fix what’s wrong but also feel as pain-free as possible. Hospitals are judged on patient satisfaction—think online reviews for healthcare.

If you’re not comfortable, the hospital’s ratings (and even funding) can take a hit. This mindset shapes how pain is handled:

Pills as the Go-To: Drug companies have spent decades convincing Americans that prescription meds are the quickest fix. Names like OxyContin, oxycodone, and hydrocodone became as familiar as aspirin.

Easy Prescriptions: Doctors often prescribe strong opioids for everything from a sprained ankle to chronic back pain, partly because patients expect fast control.

Fear of Lawsuits: If a doctor doesn’t ease a patient’s pain, they might worry about being sued for not doing enough.

This approach fueled the opioid epidemic. By the early 2000s, prescriptions for painkillers soared, leading to addiction, dependency, and thousands of overdose deaths each year.

Yet, for many Americans, the expectation remains: pain should be zapped, fast and strong.

A Real Story from the U.S.

In Chicago, one of my friends faced a tough battle with lung cancer. By the time it was discovered, it had already reached stage 4.

Her doctor sat the family down and reassured them: “We’ll make sure she stays as comfortable as possible. No one should suffer today.”

When the pain flared from spinal metastases, the hospital staff acted quickly, carefully adjusting her medications to keep her calm and at ease.

They managed her pain effectively.

2. The Japanese Approach – Caution and Low Doses

Across the Pacific, Japan’s approach to pain couldn’t be more different from that of the U.S.

Japan’s medical system is extremely cautious with opioids, shaped by strict regulations and cultural attitudes:

Strict Regulations: The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) enforces the Narcotics and Psychotropics Control Act, which tightly regulates opioid prescribing through extensive paperwork and strict oversight.

Doctors face legal and administrative pressures that discourage prescribing — not by outright prohibition, but by creating a system that strongly promotes caution.

Cultural Stigma: The word mayaku (麻薬, often translated as “narcotics” ) carries a heavy stigma, tied to crime and addiction rather than healing. This makes patients nervous about taking opioids.

Fear of Side Effects: Patients and doctors alike worry about common opioid side effects such as nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, and constipation. These concerns often outweigh the perceived benefits, reinforcing the tendency to avoid opioids.

Fear of the Drug Itself: Beyond the medical concerns, opioids carry a heavy emotional weight in Japan.

Many patients believe that opioids might shorten life, or that they are meant only for the very final stage of cancer. This fear of the drug itself often leads patients to resist opioids, even when doctors recommend them.

Gentler Options First: Doctors prefer milder drugs like loxoprofen (similar to ibuprofen) or acetaminophen, alongside non-drug solutions like pain patches or herbal remedies from pharmacies.

Tiny Doses, Short-Term: Even when opioids are used, it’s small amounts for a short time—nothing like the U.S.’s hefty prescriptions.

Holistic Alternatives: Diet adjustments, supplements, acupuncture, hot springs (onsen), massage rooted in traditional Chinese medication are go-to options.

Limited Insurance Coverage: In Japan’s national health insurance system, opioids are generally covered for cancer-related and palliative care, but not for most non-cancer chronic pain conditions. This restriction significantly limits access, even for patients who might benefit.

See also -> How to Get Medical Care in Japan as a Foreigner (Real Tips + Free Hospital List)

Real Story from Japan:

One of my relatives started coughing out of the blue but brushed it off, thinking it would pass.

One morning, she coughed up a lot of blood—shocking, right? But instead of rushing to a doctor, she headed to work for a big client meeting.

In the U.S., most people would’ve called in sick, but her endurance mindset kicked in—she didn’t want to let her team down.

That night, after another scary bleed, she finally booked a local clinic (honestly, I’d have gone straight to the ER!).

The clinic’s X-ray showed something odd, and they sent her to a hospital, where doctors diagnosed cancer.

As her condition worsened, her pain grew, but she refused opioids like oxycodone or morphine. “I don’t want to get hooked,” she told her doctor, worried the drugs would lose their power when she needed them most.

Even when she agreed to try them, she insisted on the tiniest dose possible. Once the pain eased, she stopped taking them on her own, only for the pain to return even more severely.

3. Numbers Tell the Story

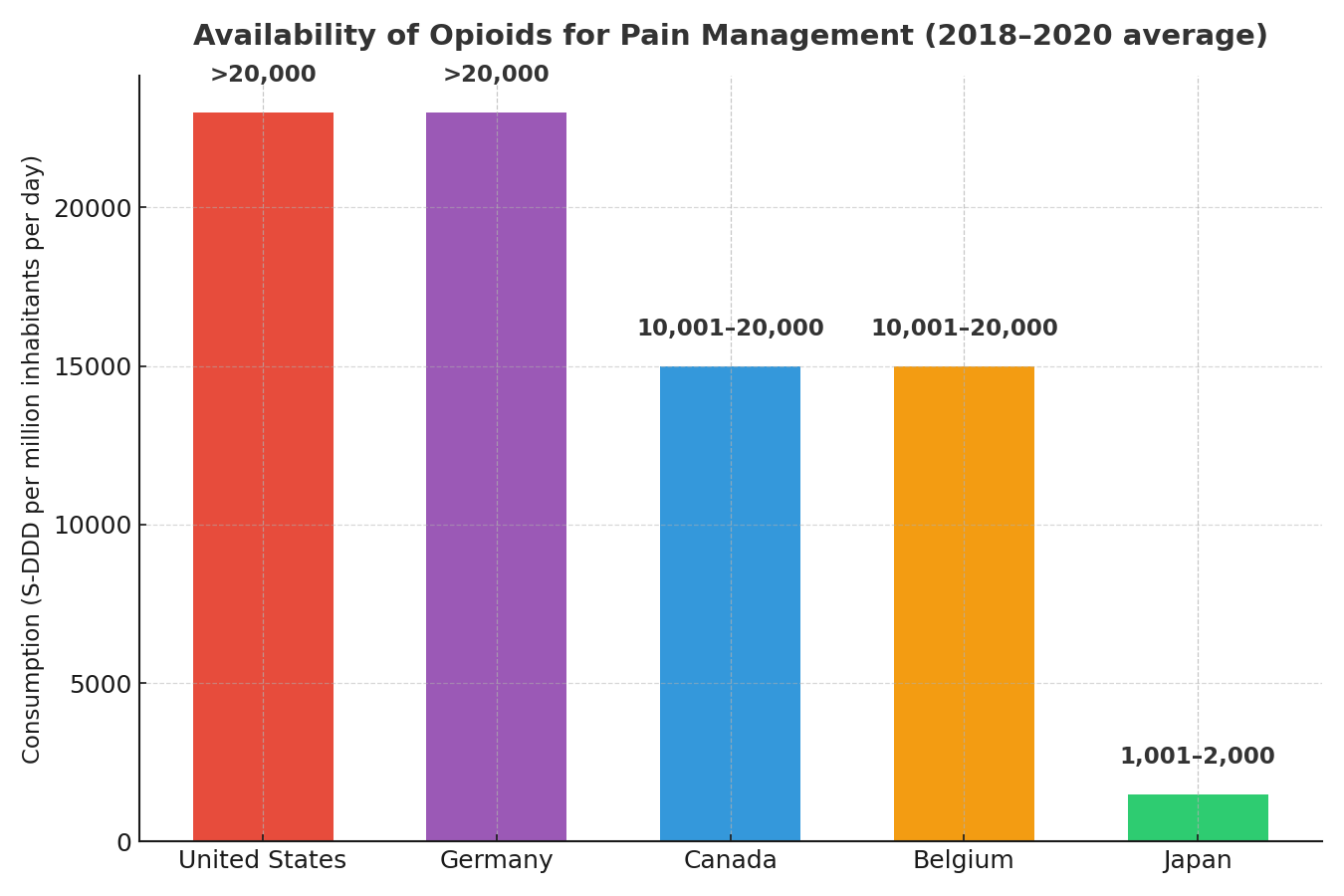

Data point: Japan is among the lowest opioid consumption countries worldwide.

Source: International Narcotics Control Board (INCB)

Figures show the average daily amount of opioid pain medicines available for medical use, measured per one million people, over the years 2018–2020.

Here is another fact:

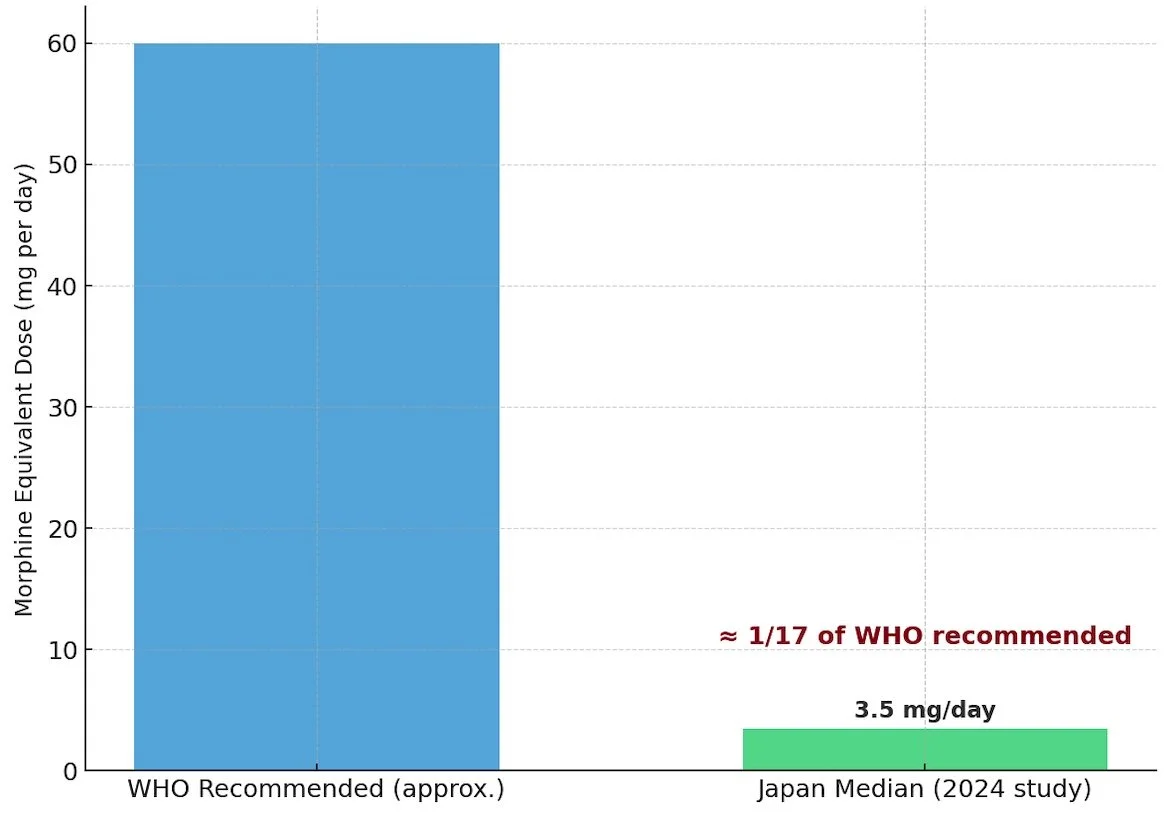

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the appropriate medical opioid use for cancer patients in the last 90 days of life at 5400 mg in morphine equivalents (approximately 60 mg per day).

However, a Japanese study found the median use to be 311 mg (approximately 3.5 mg per day), only about one-seventeenth of the recommended amount

(Source: Neuropsychopharmacology Reports, 2024- High prevalence of severe pain is associated with low opioid availability in patients with advanced cancer: Combined database study and nationwide questionnaire survey in Japan)

4. What Expats Should Know (Practical Tips)

If you are living in Japan, here are some practical steps to navigate pain management:

Bring your medical records: Ask your doctor back home to prepare a summary of your medical and medication history, including dosages. This helps Japanese doctors understand what you have been prescribed and compare it with Japanese practice.

🔹Tip: My husband’s doctor in the U.S. gave him a disk, but it took quite an effort to open it in Japan. Make sure whatever format you bring is compatible and easy to access.

Reputation and trust: Unlike in some countries, Japan does not have public doctor or hospital rating websites.

Experiences can vary widely — some patients praise excellent care, while others share stories of pain being undertreated. Because of this, it’s especially important to gather information before choosing a facility. Practical ways include:

o Palliative Care and Pain Specialists Improve Pain Control: In Japan, when palliative care/pain specialists are involved, strong painkillers (opioids) for severe cancer pain are used consistently, but without them, doctors often rely on weaker drugs.

o Check patient associations (such as the Japan Palliative Care Association or cancer support groups), which sometimes share hospital lists or recommendations.

For cancer care, leading hospitals like the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research and the National Cancer Center also host support groups. These are mostly in Japanese, but still worth trying.

o Ask for referrals from friends, colleagues, or other expats who have used the Japanese healthcare system.

Bring what works for you: OTC brands like Tylenol or Advil are available in Japan, but often in smaller doses and sometimes under different names. If you rely on a specific product, consider bringing it with you.

Know the rules for opioids: To bring opioids into Japan, you must apply for permission in advance (yakkan shoumei). See the Narcotics Control Department site).

Advocate politely: Don’t assume pain control will be automatic. Ask directly, using simple Japanese if possible. For example: “Itai desu. Motto tsuyoi kusuri arimasu ka?” (“It hurts. Do you have stronger medicine?”).

5. Steps Toward Better Pain Control

The good news is that things are slowly changing. Japan has begun to recognize the gap in pain control and is taking steps to fix it:

Faster approvals for new medicines: In the past, it could take years for drugs to reach Japan. Recent reforms have already cut approval times, and new systems are in place to speed up access to treatments for serious conditions, including cancer and palliative care.

Better incentives for companies: The 2024 drug pricing reform encourages companies to bring vital new drugs to Japan more quickly, with premiums for innovative therapies targeting serious diseases. While not specific to opioids, these changes show progress in areas such as palliative care and may open the door to better pain management options in the future.

Education and awareness - increase in opioid prescriptions for cancer patients. An article says prescription prevalence of opioids increased from 60.8 to 65.9% (5.1%) from 2010 to 2019.

Challenges remain — such as regional differences— but the direction is clear. For expats and Japanese patients alike, this means there’s reason for hope: comfort and dignity at the end of life are moving higher on the agenda.

6.FAQs: Pain Control in Japan

Q1: Is opioid use a big topic in Japan?

A: Not really in the public eye — it’s more of a “known issue among specialists.” But if you check PubMed, you’ll find many recent research articles on opioid use in Japan, which shows the medical community is paying attention and pushing the conversation forward.

Professor Keiichi Nakagawa of the University of Tokyo also raised the issue in a 2025 Nikkei, noting that medical opioid use for cancer pain in Japan remains extremely low.

That combination of research and public commentary is an encouraging sign that awareness is growing.

Q2: Will I get opioids after surgery in Japan?

A: Yes, opioids are commonly prescribed after surgery. However, the type and amount prescribed can vary depending on the hospital and its location. Always discuss pain control directly with your doctor so you know what to expect.

Q3: Can I bring my own pain medication to Japan?

A3: Some OTC medications are fine, but strong narcotics require special import permission (yakkan shoumei). Always check Japanese customs rules before bringing prescription opioids.

Q4: Do Japanese people suffer more because of low opioid use?

A4: Studies show higher rates of severe, untreated pain in cancer patients, with only 311 mg used vs. WHO’s 5400 mg recommendation.

Q5: How can I prepare for pain management as an expat in Japan?

A: Use clear, structured communication. For example, rate your pain on a 1–10 scale (“It’s an 8 out of 10”) and describe your symptoms in order, like a short timeline of when they started and when they feel worst.

If possible, write this down in a simple report—or ask a family member to document it—so the doctor can read it directly. This helps overcome language barriers and fits the logical style many Japanese doctors prefer.

My husband used this method with his cardiovascular specialist, and it worked well.

Always consult your doctor for the pain control options that best fit your situation.

7. Wrap Up: A Hopeful Path for Pain Control in Japan

Japan’s careful approach to pain management reflects its culture of caution, and it’s helped avoid the opioid addiction crisis seen in the US, where overdose rates are far higher.

But for someone like me, with a moderate pain tolerance, the thought of enduring severe pain—especially in serious conditions like cancer—feels daunting.

I’ll never forget my time in a US hospital, where doctors prioritized wiping out my friend’s pain with strong, fast-acting medications.

Or when my husband had heart surgery: he was in the ICU with a dedicated nurse watching him closely, yet he felt minimal pain and was discharged in just a few days, incision still fresh!

With Japan’s aging population pushing for better care, I’m hopeful that pain control will keep improving, making life easier for everyone, whether you’re local or visiting.

Disclaimer: This reflects cultural and systemic trends, not medical advice. Always consult a doctor for pain management.

See also:

Adjustment Disorder in Japan: How to Navigate Work, Stress, and Your Rights

You Need CPAP in Japan? No Problem – Here's How

Referral:

Expediting Drug Development in Japan: A PMDA Perspective (PubMed)

PMDA Report on Priority Review Products (PDF, PMDA)

Review of Japan’s FY2024 Reform – Inbeeo (2025)

Reversing the Tide: Japan’s Promising FY2024 Drug Pricing Reform – Health Advances