Can Your Employer Stop You from Switching Jobs in Japan? Non-Compete Rules Explained

Worried your employer could block your next career move in Japan? Non-compete agreements (競業避止義務, kyogyo-hishi-gimu) are common for professionals here, but their enforcement is far from guaranteed.

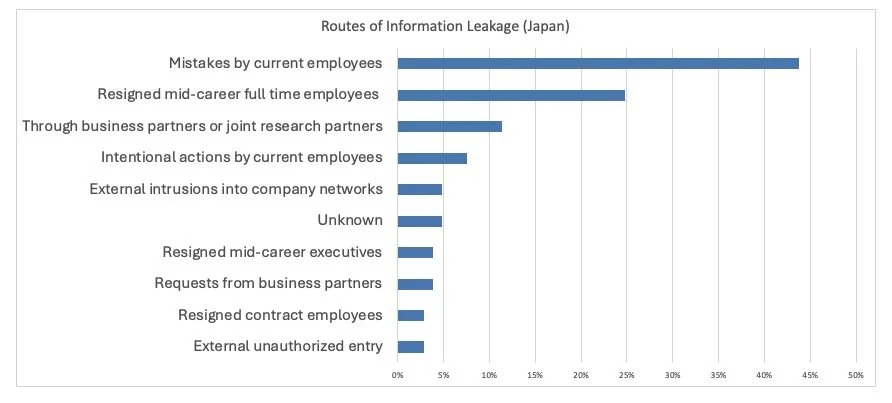

In fact, leaks by former employees are a top concern for Japanese companies (See Section 1 for more detail), making non-competes a critical issue for both employers and expats.

Courts apply a strict reasonableness test, balancing employer restrictions against your constitutional right to choose your occupation (Article 22).

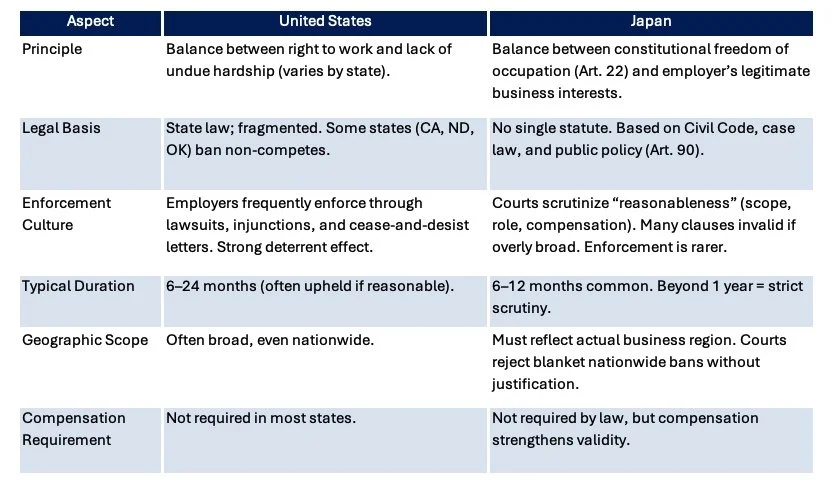

In the U.S., non-competes are under scrutiny—some states like California ban them outright, while others enforce them aggressively.

This post dives into Japan’s non-compete rules, their enforceability, and what they mean for your career mobility.

This blog covers:

1. What Non-Compete Agreements Mean in Japan

2. Legal Basis and Enforceability

3. Japan vs. U.S. : Key Differences

4. Real Risks for Expats: Visa, Language, and Cultural Traps

5. Non-Solicitation Clauses: A Related Risk

6. Practical Steps to Protect Yourself + Q&A

7. Wrap up

1. What Non-Compete Agreements Mean in Japan

Non-compete obligations (競業避止義務, kyogyo hishi gimu) are the duty of employees to refrain from activities that compete with their employer’s business.

This may involve joining a competitor, starting a rival company, or misusing confidential information, intellectual property, or trade secrets to the benefit of another organization.

Where they appear

Non-compete clauses often show up in one or more of the following:

Rules of employment (就業規則)

Employment contract or offer letter

Letter of pledge, sometimes required at the time of retirement

They apply in two phases:

During employment

A duty of loyalty (Labor Contract Act, Article 3) applies, even without a written clause.

You can’t: Start a rival company or moonlight at a competitor.

Directors: The Companies Act (Article 356) bans competitive acts without board approval.

🔹Tip: For side jobs, get written employer approval to avoid conflicts, especially if you hold significant responsibilities or have access to confidential information.

After employment

Non-competes may block joining competitors or launching rival businesses.

Courts interpret these narrowly, balancing company interests (e.g., trade secrets) with your right to choose an occupation.

Written clauses are key but often less enforceable than employers assume.

Typical Use Cases

Senior managers (e.g., C-level, department heads)

Engineers/R&D (e.g., Quality engineer)

Finance professionals (e.g., analysts)

Sales roles with access to client lists or pricing structures

✅ Information leaks are a major concern for employers. According to the 2024 February “Protection of Intellectual Property Hand Book” after mistakes by current employees, leaks by former employees who switched jobs are among the most common sources of data breaches.

To address this risk, companies are encouraged to use non-compete agreements and project-specific non-disclosure agreements (NDAs).

Difference from NDAs

NDAs (non-disclosure agreements): Aim to prevent leaks of confidential information.

Non-competes: Restrict where and for whom you can work.

These are often bundled together, but they are legally distinct.

2.Legal Basis and Enforceability

Japan does not have a specific “Non-Compete Act.” Instead, enforceability is based on a combination of legal principles and court precedents:

Constitution Article 22: Guarantees occupational freedom. Overly broad non-competes risk violation.

Labor Contract Act (Article 3): Mandates “good faith.”

Civil Code (Article 90): Voids contracts against public policy.

Case Law: Courts assess “reasonableness.”

Enforceability Criteria

Courts evaluate post-employment non-competes using three main criteria:

Legitimate Business Interest: Must protect specific assets (e.g., proprietary AI models).

Scope:

Job Type: Industry-wide bans are weak; role-specific limits are stronger.

Geography: Nationwide bans often fail; city/region limits are better.

Duration: 6-12 months is reasonable; over 2 years risks invalidation.

Compensation: Financial compensation (e.g., 3-6 months’ salary) boosts enforceability. No compensation often voids clauses. Clauses with no compensation are often voided, especially if combined with broad scope or long duration.

Consequences of Breach:

Reduced or forfeited retirement allowance

Damages claims

Court injunctions to stop competitive work

Real Cases:

American Life Insurance (Tokyo District Court, 2012)

The non-compete clause in this case was judged too broad — it covered an excessively wide range of work, lasted too long, and applied nationwide. On top of that, the company did not provide sufficient compensation. The court ruled the clause was unreasonable and violated the employee’s right to choose an occupation.

Result: the company lost and was ordered to pay the employee’s unpaid retirement allowance.

Yamada Denki (Tokyo District Court, 2007) -> Interesting case where a company won.

Here, the employee was a senior manager with access to sensitive information. The court found there was a legitimate reason to impose a non-compete. Even though compensation was not adequate, the clause in the retirement pledge was still considered valid.

Result: the company won, and the employee was ordered to pay damages (half of the retirement allowance plus one month’s salary).

✅What I’ve Seen Firsthand

In practice, post-employment non-competes in Japan are recognized only in limited situations.

Most people simply move to another company in the same industry where their skills are valued. Employees are not legally required to disclose their new employer when leaving, and most don’t.

Companies usually discover a former employee’s new employer later, at which point they may send a warning letter to you.

Lawsuits are rare, but fear of intellectual Property leaks keeps non-competes on the agenda for many Japanese firms.

This reality makes Japan very different from the U.S., where aggressive enforcement and lawsuits are common.

3.Japan vs. U.S. : Key Differences

Real Story

When I was in Chicago, a friend of mine—a highly skilled quality control specialist—was blocked from starting at a new employer because of a non-compete clause. Fortunately, the new company valued him enough that, on his first day, they compensated him for the restricted period with a sign-on bonus.

Here in Japan, I have also made the same kind of offer. In reality, a gap of six to twelve months can make a big difference—information can quickly become outdated during that time. If you are truly valued, companies are often willing to pay for your expertise.

🔹For foreign professionals, this means that your market value may give you leverage to negotiate compensation if a non-compete is enforced

Non-Competes Under Scrutiny

The strong shift is happening in the U.S., where several states have banned non-competes outright, while others continue to enforce them aggressively.

Japan, by contrast, takes a case-by-case approach, with courts often striking down overly broad or unpaid clauses.

While the pace differs, the debate over worker mobility and innovation is global.

4.Real Risks for Expats: Visa, Language, and Cultural Traps

Expats face unique challenges:

Language Barriers: It is critical to fully understand non-complete, non-solicitation and non-disclosure agreement. If non-complete clause doesn’t make sense, ask if any amendment is possible.

Visa Risks: Work visas (e.g., Engineer/Specialist in Humanities) tie to specific roles. A non-compete could limit job options, risking visa renewal.

Cultural Expectations: Japanese firms may view competitor moves as “disloyal,” even without enforceable clauses.

Legal Costs: Challenging a non-compete costs JPY300,000-500,000, tough for expats.

✅My HR Experience:

When you join a new company, it’s common to find a non-compete clause included in the hiring documents. At that stage, most people are simply excited to have landed the job, so they sign without much hesitation.

From my experience, walking new hires through offer letters and/or employment contracts, few—whether foreign or Japanese—ever asked for clarification, amendments, or removal of the non-compete clause.

Many feared that raising such questions would make them look as if they were already planning their exit.

Asking questions about non-competes doesn’t mean you’re planning to quit—it shows you understand your rights. In fact, it gives us the impression that you take contracts seriously.

5. Non-Solicitation Clauses: A Related Risk

Non-solicitation clauses, often bundled with non-competes, prohibit:

Recruiting former colleagues

Soliciting clients from your old company

These are easier to enforce, as they protect direct business relationships.

Real story:

A salesperson resigned and was approaching his final day at the company.

One day, we discovered him in a conference room taking photos of business cards he had collected during his employment, using his personal iPhone.

Under our rules of employment, this was a violation—and it could also raise issues under laws such as the Act on the Protection of Personal Information and the Unfair Competition Prevention Act.

Taking client contacts with you can violate both company rules and Japanese law

6. Practical Steps to Protect Yourself + Q&A

Steps to Take

Review Contracts: Review contracts carefully to understand clauses beyond non-competes, such as non-solicitation and confidentiality agreements.

Negotiate Early: Propose shorter terms (e.g., six months) or a narrower scope (e.g., specific technologies), and explain your visa risks—do this before signing.

Some companies may offer ‘garden leave’ (paid restriction periods), but this is usually reserved for high-value, high-risk employees.

Keep Records: Save contracts, emails, and exit talks.

Consult Experts: Use English-speaking attorneys or municipal foreigner consultation centers.

Explore Alternatives: Apply skills in non-competing fields (e.g., AI in education).

FAQs for Expats

Here are the most common questions foreign professionals ask about non-competes in Japan

Q1-a: I’m on a Specified Skilled Worker visa. Will my employment contract include a non-compete clause?

A: Generally no. These contracts are standardized and focus on wages, working conditions, and support services. Non-competes are rare and would likely be unenforceable for these roles, since there’s usually no access to trade secrets or proprietary know-how.

Q1-b: What’s the real restriction then?

A: The visa itself. If you leave your employer, you must quickly find another job in the same industry to maintain your visa status. In practice, immigration rules limit mobility more than non-compete clauses.

Q2: Can I work for a competitor in Japan if my contract has a non-compete?

A: It depends. If the clause is narrow, tied to protecting trade secrets, and includes compensation, it may be enforceable.

Broad or unpaid clauses are often struck down under Article 22 of the Constitution. Always check duration, scope, and compensation before signing, and consult an attorney if unsure.

Q3: What happens if I move outside Japan?

A: Japanese courts generally cannot enforce a non-compete if you work overseas, unless your former employer has substantial operations in that country.

For example, if you join a competitor in the U.S. or Europe, a Japanese non-compete is unlikely to apply unless the company can prove global harm (such as misuse of trade secrets).

That said, many contracts include a governing law or jurisdiction clause (e.g., “This contract is governed by Japanese law”).

In practice, enforcement abroad is rare, but these clauses can still give employers a basis to send warning letters or attempt cross-border claims.

🔹 Tip: Keep records of your contract and exit discussions, and let your new employer know about any non-compete so they can support you if needed.

Q4: Will I get paid during the non-compete period?

A: Not necessarily. Japan does not require compensation for non-competes, unlike the EU.

Courts often strike down unpaid restrictions, especially those lasting more than a year, while paid clauses (e.g., 3–6 months’ salary) are more likely to stand.

In practice, most employees move directly to competitors, and compensation is considered only in rare cases, usually for senior managers or those with access to confidential information.

Q5: Do non-compete clauses apply to freelancers or contractors?

A: Rarely. They’re harder to enforce because courts prioritize the freedom to work. A narrow, project-specific clause might stand, but broad ones usually don’t.

🔹 Tip: Clarify in writing whether a non-compete applies to your freelance work.

Q6: What happens if I refuse to sign a non-compete?

A: You can’t be forced to sign. Refusing at resignation may strain relations, but it’s not legally required. Refusing during hiring could affect the offer.

🔹 Tip: Explain concerns (e.g., visa or career mobility) to show good faith.

Q7: What should I do if I receive a warning letter from my former employer?

A: In Japan, a warning letter about a non-compete can feel intimidating, but it is often more of a reminder than the start of a lawsuit. Employers may send it directly to you or to your new employer. Don’t panic.

If the letter is general and does not point to specific misconduct, respond politely in writing—acknowledge receipt.

If the letter raises concrete allegations, discuss it with your current employer and consult an attorney promptly.

🔹 Tip: Keep all correspondence. Align your response with your new employer, and involve an attorney if the letter cites specific issues.

7.Wrap-Up:

At its core, the debate around non-competes is about balance.

On one side is the right to work, freedom of occupation, and the principle that employees should not face undue hardship when seeking new opportunities.

On the other is the need for companies to protect intellectual property, confidential information, and legitimate business interests.

Striking the right balance between those is difficult. The tension between protection and mobility is here to stay.

References

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2024, April 17). Human resources working group materials

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI). (2024, Feb). Protection of confidential information hand book

Tokyo Labor Bureau. Guide to Advisory Service for Foreign Workers

Related Posts:

Employment Contracts in Japan – What You Need to Know

Overtime in Japan: What’s Legal, What’s Not, and How to Protect Yourself