Raising Kids in Japan: Costs, Subsidies, School Choices & Real Challenges for Foreign Parents

Children learn not only through school, but through hobbies, relationships, digital communities, and—if they are lucky—experiences such as study abroad.

Japan offers one of the safest and most structured learning environments in the world, but it also comes with unique expectations, limited flexibility, and early academic pressure.

This guide highlights the strengths of the Japanese system, the costs involved, the government support available, and the real challenges foreign parents should be prepared for.

For the basic structure of the Japanese school system, see my separate guide:

Japanese Education System 101: A Practical Guide for Families and Students

This blog covers:

1. Why Japan Still Ranks Near the Top of Global Education

2. Real Education Costs – From Age 3 to University Graduation

3. Government Support You Can Actually Use as a Foreign Resident

4. Choosing Public, Private, or International School

5. Things to Consider

6. Navigating Expectations & Practical Tips for Foreign Parents

7. Q&A

8. Wrap up

1. Why Japan Still Ranks Near the Top of Global Education

Japan sometimes makes headlines for exam pressure, but its strengths are real and internationally recognized.

Strong academic fundamentals

In PISA 2022, Japanese 15-year-olds ranked:

5th in mathematics

3rd in reading

2nd in science

High-quality classes that put strong emphasis on foundational academic skills

Japan’s national curriculum is unified nationwide, which means students receive the same high-quality education regardless of region or family income. The curriculum places a strong focus on developing students’ knowledge base and critical-thinking skills—one of the key reasons behind Japan’s strong PISA performance.

Daily routines for discipline

From grade 1, students clean classrooms, serve school lunch, and rotate leadership roles. These routines cultivate discipline, punctuality, responsibility, and group cooperation—qualities that Japanese employers consistently value.

Every public-school student receives a device

Through the GIGA School Program (completed in 2021), all elementary and junior-high students receive their own tablet or laptop with high-speed Wi-Fi. This ensures equitable access to digital tools.

Exceptional safety and independence

It is common to see 6-year-olds walking to school alone, or 10-year-olds returning home from cram school (Juku/塾) at 9 p.m. Japan remains one of the safest countries in the world, allowing children to develop independence earlier.

Clear academic pathways—if your family wants them

Private integrated junior–senior high schools offer strong academic outcomes and established routes into top universities. However, this path often begins around elementary grade 3, when many children start after-school cram programs.

Japan combines structure, equality, and discipline in ways that many foreign parents appreciate. Still, no system is perfect—the trade-offs appear in later sections.

2. Real Education Costs – From Age 3 to University Graduation

Japan is affordable if you stay within the public system, but costs rise sharply with private or international schools.

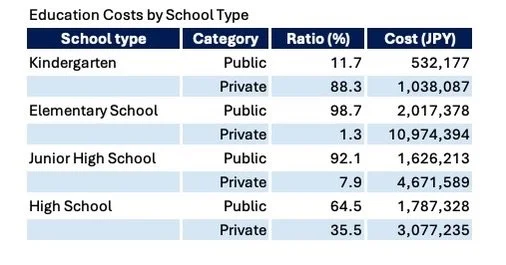

According to the Ministry of Education’s 2023 “Survey on Children’s Learning Expenses,” the total cost of education from kindergarten through the third year of high school (a 15-year period) is:

This gap explains why many Japanese families begin financial planning as early as preschool.

International schools typically cost JPY2–5 million per year, not including admissions fees or technology fees.

Education Costs for Four Years of University

How much does university cost over four years?

According to the Japan Finance Corporation’s 2021 Survey on the Actual Burden of Educational Expenses, the total education cost for four years of university is as follows:

F.Y.I. Private medical schools typically cost approximately JPY18–40 million for the full six-year program.

Additional Costs: Cram School, Lessons, and Activities

Beyond school tuition, Japanese families invest heavily in after-school learning and extracurricular activities. According to MEXT, households spend significant amounts on:

Cram school/Tutor – essential for private school entrance exams

English conversation classes (JPY8,000-12000 per month)

Piano (JPY7,000-15,000 per month), violin, or other music lessons

Sports programs (JPY5,000-9,000) such as swimming, soccer, gymnastics, karate, dance

Art, culture, and experience-based activities

For many families, these expenses can add JPY10,000–JPY20,000 per year in elementary school, rising to JPY150,000–JPY400,000 per year in junior high, especially during exam preparation years.

Source (Chart 6/Japanese)

3. Government Support You Can Actually Use as a Foreign Resident

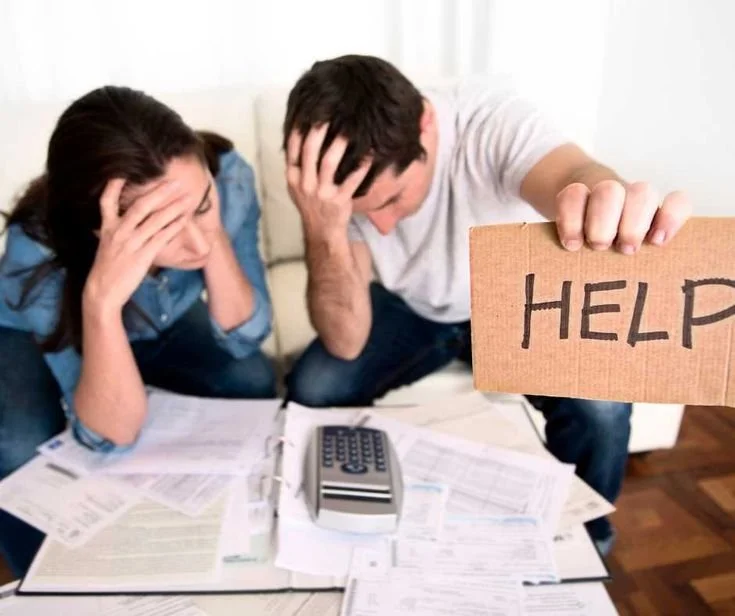

Japan has significantly expanded family support policies over the past decade, and these programs can meaningfully reduce the cost of raising children—especially for foreign families. To begin with, tuition at public elementary, junior high, and high schools is free.

Free Early Childhood Care/Tuition

Child Care fee is free for ages 3–5 (including schools for children with developmental support needs) in licensed childcare and kindergarten. Low-income families with younger children may receive full fee waivers.

For children ages 0 to 2, childcare fees are waived for households that are exempt from resident tax.

Junior High School Tuition Support (Tokyo)

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government is accepting applications for its Tuition Reduction Program for Private Junior High Schools and Private High Schools for FY2025.

⚠️NOTE: This program may be revised or changed in future fiscal years.

Upcoming: High School Tuition Support

Currently, public high school tuition is effectively free but not all (extra remain), and private high schools receive limited subsidies.

From FY2026, the income cap for private school tuition support is expected to be removed, and subsidy amounts may increase to roughly match the national average tuition level.

⚠️NOTE: These changes are planned but not yet finalized.

Higher Education Support Program

Since April 2020, the Ministry of Education has offered the Higher Education Support Program, which helps students enroll in universities (two- or four-year programs), vocational schools, and technical collegesdepending on family income. The program provides non-repayable grants and reductions or waivers of tuition and admission fees.

From FY2024, support has expanded for families with three or more children and for middle-income students in private science and engineering programs.

Starting in FY2025, tuition and admission fees will be free for students from multi-child households (from 3 or more) regardless of household income.

⚠️ NOTE: Students must meet academic requirements such as attendance rates and earned credits.

Under 3 years old: JPY15,000 (JPY30,000 for the third child and beyond)

Ages 3 through high-school age: JPY10,000 (JPY30,000 for the third child and beyond)

Starting from the October 2024 revision, the allowance is provided regardless of household income. To receive the Child Allowance, you must apply, so be sure to apply at your local city or ward office.

Child Medical Subsidies (医療費助成)

Most municipalities cover nearly all medical costs for children through junior high, and in some areas high school. A doctor visit may cost only a few hundred yen.

Apply at your local city or ward office for a Child Medical Certificate. Showing it at clinics/hospitals reduces or eliminates your out-of-pocket costs, but services not covered by insurance—such as checkups, vaccinations, or private room fees—are excluded.

After-school Programs (学童保育)

Available for grades 1–6. Typical fees: JPY5,000–JPY20,000 per month. Helpful for dual-working households, though availability varies.

NEW: Child-Rearing Support Contribution (子ども・子育て支援金制度)

Beginning 2026–2028, small contributions added to public health insurance premiums:

The average monthly contribution is JPY250–JPY450, but the amount varies by health insurance type.

For employee health insurance, excluding dependents, the cost per insured worker is about JPY450–JPY800 per month (JPY5,400–JPY9,600 per year).

Funds are legally dedicated to child-related programs mentioned above.

Other support

Japan provides a range of services for foreign families, including free or low-cost counseling, parenting consultations, and support for children with disabilities—such as early intervention and developmental screenings. These services are available through local child–family support centers and municipal offices.

Foreign parents can access these services through local child-family support centers, public health offices, and municipal consultation windows.

For more details, see the sites in English. Full of good information.

Children and Families Agency (CFA): Child and Family Support Services Overview (English PDF)

CFA Official Website

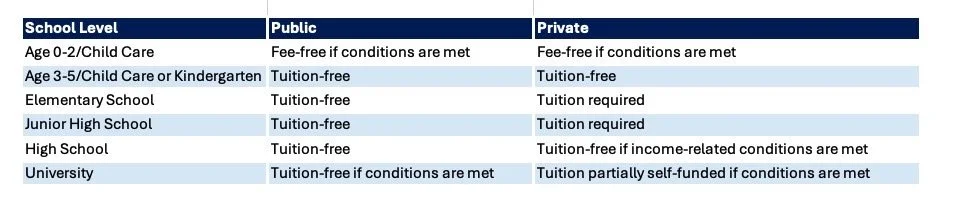

4. Choosing Public, Private, or International School

There is no single “best” path. Each option fits different family goals.

Public schools

Low cost and locally grounded

Limited language support

Emphasize group norms

Quality can vary significantly by region, especially at the junior high and high school levels. In areas with many private school options, academic standards at public schools may differ greatly—so it is important to research the quality of individual schools carefully.

Private schools

Strong academic pathways to top universities

More structured and competitive

High tuition

Requires early cram school preparation (from age ~9)

Best suited for families committed to academic rigor. It is also important to note that not all private schools are highly competitive—academic pressure and culture vary widely by school.

International schools

English or bilingual curriculum

Smaller classes, more flexible support for neurodiversity

High cost (JPY2–5 million/year)

Limited integration into Japanese society

Hybrid paths

Parents often mix options:

Public school + English cram school or tutors

International school until literacy strengthens, then transition

Study abroad programs in high school or summer

Japan offers more pathways than many parents initially realize.

5. Things to Consider

Even with its strengths, Japan’s education system poses challenges—especially for children who are non-native speakers, neurodivergent, or thrive in non-traditional learning environments.

Language support is limited

Most municipalities offer JSL (Japanese as a Second Language) instruction, but typically only a few hours per week. Staffing and funding vary widely, and some areas lack trained teachers altogether.

Bullying and school refusal/Hikikomori

Japan reports rising cases of bullying and school refusal/Hikikomori. Group conformity can make newcomer children feel isolated. Parents should document concerns, speak with teachers early, and understand escalation routes.

Intense university exam culture

Between January and March, high-school seniors take high-stakes entrance exams. The system emphasizes memorization and test performance rather than holistic evaluation.

Unlike the U.S., which considers essays, grades, activities, and recommendations, Japan’s entrance exams are largely one-shot opportunities. Some children thrive; others find the pressure overwhelming.

Transfer difficulties

Mid-year transfers are rare and socially challenging. Transitions from international to Japanese schools require strong Japanese literacy; the reverse is easier academically but costly.

Neurodiversity

Japan’s mainstream system prioritizes uniformity.

Support for ADHD, ASD, dyslexia, or other neurodivergent needs varies by municipality and may be limited.

Foreign parents often combine multiple approaches, such as:

International schools

After-school therapy or coaching

STEAM or coding programs

Online or hybrid learning

A balanced strategy—advocating within the school while building external support—tends to work best.

Alternative & digital learning

Some children excel in online learning communities, coding clubs, digital arts, e-sports teams, or metaverse-based platforms.

These environments can offer creativity, global interaction, and a sense of belonging that traditional classrooms may not provide.

Teacher Challenges and Impact on Families

Teachers face expanding responsibilities: integrating IT, teaching programming, managing paperwork, and supervising clubs on weekends. Overtime is common, and English proficiency varies.

For parents, this means:

Communication is often via written notices, not conversation.

Meetings may assume familiarity with Japanese school culture.

Teachers may lack time for individualized academic or language support.

Lastly, public school enrollment is not automatic.

Foreign children are not legally required to attend school, but public schools are open to all families. Parents must apply through their local city or ward office. Availability of JSL support and learning support staff varies widely, as these resources depend heavily on each municipality’s staffing and funding.

Understanding these constraints helps set realistic expectations and improve parent–school communication.

6. Navigating Expectations & Practical Tips for Foreign Parents

Foreign parents often find that the unwritten rules of Japanese schools are harder to navigate than the academics themselves.

Understanding Expected Parental Involvement (Especially for elementary school period)

Japanese schools expect parents to play an active role in daily school life. This typically includes:

Checking homework and daily communication notebooks

Establish a habit of having children manage their own home learning

Participating in PTA roles on a rotating basis

Responding promptly to school notices and forms

Schools typically have rulebooks—be sure to review and understand them carefully.

It is also important to know that grade repetition is extremely rare during compulsory education. Even with low grades or limited attendance, students usually advance automatically.

If your work schedule or Japanese ability makes these expectations difficult, it is best to communicate clearly and early with the school.

Communicating with Teachers

Effective communication does not require perfect Japanese.

Short notes written in simple Japanese are often best

For important meetings, consider bringing a bilingual friend or support person

Ask specific questions rather than open-ended ones to get clearer answers

Understanding teachers’ workload and time constraints helps build cooperative relationships.

Supporting Your Child Emotionally

Children growing up between cultures may feel pressure to “fit in” at school while being different at home. Make space for regular conversations about identity, stress, friendships, and self-esteem, and reassure them that it is okay to belong to more than one world.

For Neurodivergent or Non-Traditional Learners

Support for ADHD, ASD, dyslexia, or other learning differences varies by municipality. Many families combine school-based support with outside resources:

Supplemental therapy or coaching

Digital, creative, or STEAM-based learning platforms

Alternative schooling or hybrid models

In some cases, children who do not attend school regularly can still have their learning officially counted as attendance through approved ICT-based home learning programs.

Official guidance (Japanese):

Choosing a different learning environment is sometimes the healthiest option.

Before Enrollment: What to Prepare

Having information ready reduces misunderstandings later. Prepare:

Vaccination records

Allergy and health notes (Japanese/English if possible)

Emergency contact list

A short profile describing your child’s strengths, learning style, and any support needs

Language Support & Schools Friendly to Foreign Students

YSC Global School (NPO Youth Support Center) – Your sample; specialized Japanese & subject tutoring for foreign-root children.

Plus Educate (Certified NPO) – Professional education support for foreign-root kids, including Japanese classes & teacher training.

Metanoia (NPO) – Supports immigrant/foreign-root children with education & integration.

Kids Door (Certified NPO) – Learning support for foreign-root children.

Tabunka Kyosei Center Tokyo (Multicultural Coexistence Center) – Saturday learning support classes for elementary+ kids.

(See child projects section)Nihongo NPO (Hamamatsu-based) – Japanese classes & child learning support.

Jabora NPO (Hamamatsu) – Child-focused Japanese education volunteers.

Katariba (Certified NPO) – Projects for foreign-root high school students.

Online/Virtual/Metaverse-Focused (For Remote or Innovative Learning)

Metaverse-specific groups for kids are rare (mostly adult-oriented or general), but here are online/virtual options:

JPLT Online Japanese School – Free metaverse campus (virtual world) for Japanese learning; group classes, 1-on-1, community lounge. World’s largest free virtual Japanese platform. - Metaverse campus info

7. Q&A

Q1. Can a child with little Japanese attend public school?

A1. Younger children often adapt quickly, especially in kindergarten and the early elementary years. Older children—particularly those entering junior high or above—face much steeper challenges without basic reading and writing skills. Many families assume that “things will work out” simply by enrolling in a public school, but this expectation is often unrealistic.

That said, there are families who have successfully navigated public schools with limited Japanese. In most of these cases, parents—often with multiple children—were deeply involved: communicating regularly with teachers, closely monitoring academic progress, and providing daily learning support at home. These outcomes were the result of sustained parental commitment rather than the school system alone.

For families who cannot provide this level of support, a phased transition or an international school may be a more practical option.

Q2. Do we have to send our child to cram school?

A2. No—not at all. Many families choose not to use cram schools if they are satisfied with local public schools and are not aiming for competitive private junior high schools or top universities.

That said, especially before university, some families find it helpful to enroll their children in supplemental programs in their native language. These environments allow children to build friendships without language barriers, ask questions freely, and stay academically on track—often with much less stress.

Q3. It seems my child is being bullied. Where should I seek help?

A3. First, speak with your child’s homeroom teacher. You may also consult the local board of education, a child consultation center, or an NPO that handles cases involving foreign children. If you suspect bullying, it is strongly recommended to seek advice from these organizations as early as possible.

8. Wrap Up

Raising children in Japan can be incredibly rewarding for foreign families — world-class academics, exceptional safety, generous government support, and a culture that truly values education.

But success comes from understanding the system, planning for costs and challenges, and choosing what best suits your child’s unique needs.

My own son and daughter studied abroad — not easy, especially with the language barrier — but those challenges built real confidence and lifelong experiences.

If you’re raising kids here (or planning to), what’s your biggest surprise or challenge? Share in the comments below — I read them all and love hearing your stories. It helps me make better guides for families like yours. Navigator Japan is always here if you need help. Welcome to the journey!

See also for family leave and others:

Paid and Unpaid Leave in Japan, Vol. 1 – Make the Best Use of It

Paid and Unpaid Leave in Japan, Vol.2 – Make the Best Use of It