Japan's Workforce Rebalance: The Mid-Career Foreigner's Strategic Edge

The end of the year—around bonus season or the holidays—is when many people finally have the time and mental space to reflect. Some feel dissatisfied. Others are doing well but quietly ask themselves whether staying put is still the right choice.

For foreign professionals, these thoughts come with additional weight: visa constraints, language barriers, and uncertainty about how Japan’s job market is actually changing.

Before making a move, it is worth stepping back. Japan’s labor market is not simply “tight” or “slow.” It is structurally shifting—and understanding that shift is what allows good decisions.

This article is a framework for mid-career foreign professionals who want to evaluate opportunity, risk, and long-term career value in Japan.

This article covers:

1. What’s Really Happening in Japan’s Job Market

2. Why Motivation Matters More Than Ever

3. Preparation Is Not About Tactics—It Is About Fit

4. The Structural Advantage—and Constraint—of Being Foreign

5. Timing Is About Risk, Not Speed

6. Retention Logic Has Changed—And You Should Adjust Accordingly

7. Using Recruiters as Strategic Intermediaries

8. Legal and Visa Awareness as Risk Control

9. The Psychological Traps to Avoid

10. Q&A

11. Wrap up

1. What’s Really Happening in Japan’s Job Market

At first glance, Japan’s labor market appears stable. Total employment remains near historic highs, and headline numbers are often cited as evidence that the economy is holding up.

But aggregate figures hide more than they reveal.

When employment data is broken down by age and gender, a clear structural pattern emerges.

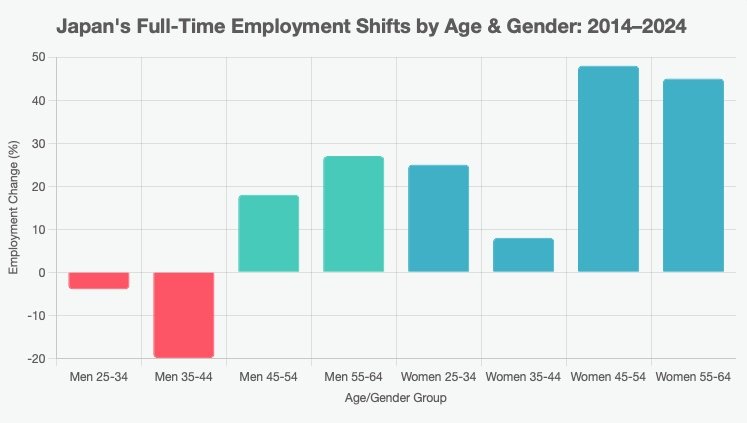

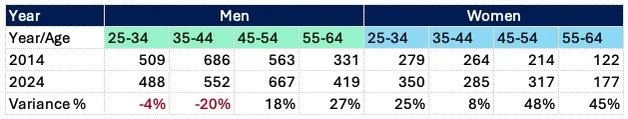

The chart illustrates percentage changes in full-time employment by age and gender (2014–2024), revealing clear divergence across groups.

The most notable shift is the sharp decline in prime-age men, particularly those aged 35–44, who have traditionally formed the core of Japan’s corporate workforce.

In contrast, full-time employment among women has increased across all age groups. However, the total number of female employees in each age group remains lower than that of men.

Growth is especially strong among women aged 45–64, indicating a structural rise in mid- and late-career women participation.

Although older men employment has also increased, this growth occurs later in the career cycle and does not compensate for the loss in the prime-age men pipeline.

As a result, workforce stability is being maintained not by expansion at the core, but by greater participation from women and older workers.

For foreign professionals, this context is essential. Hiring demand is no longer driven only by technical skill shortages. It is shaped by demographic reality—and by the need for people who can contribute, adapt, and stay.

Source:

Statistics Bureau of Japan, Labor Force Survey 2024

Data Reference: Full-Time Employees by Age and Gender (Millions)

2. Why Motivation Matters More Than Ever

Many job changes fail because the reason for changing jobs is unclear.

In Japan’s current environment, switching roles impulsively is risky. Yet job boards and recruiting platforms encourage comparison rather than clarity. It becomes easy to chase signals such as:

The salary is higher.

The company name sounds impressive.

There must be a better culture somewhere.

These reasons are understandable—but insufficient.

Before applying, it is worth asking:

What specifically is no longer working in my current role?

What kind of work still gives me energy, even when it is demanding?

Am I trying to build a long-term career in Japan, or is this experience transitional?

What do I want to accomplish by this job hunting?

Without clear motivation, mismatches occur on both sides. In a market where retention matters, this is increasingly costly—for you and for the employer.

3. Preparation Is Not About Tactics—It Is About Fit

Successful job changes are not driven by the volume of applications sent. They are driven by information, alignment, and retention logic.

Preparation therefore starts with self-analysis. This does not require complex frameworks—practical reflection is often more effective:

Review past performance evaluations or other objective feedback

Identify responsibilities or projects that were difficult but rewarding

Recognize where you consistently add value

Clarify what you want from your experience in Japan—long-term career development, skill accumulation within Japanese organizations, or sustained engagement with Japanese business systems

This level of clarity strengthens interview credibility and reduces post-hire friction—both of which matter more in a market where replacement is costly.

Equally important is an alignment check with the role and organization:

What responsibilities actually sit behind the job title?

How are decisions made in practice?

How is performance evaluated—and by whom?

What level of Japanese is required in day-to-day operations?

Taken together, this preparation allows you to explain why you want a role, not just that you want it.

Real story:

I once worked with a highly experienced Japanese professional who wanted to move from a stable domestic company to a foreign firm. During the interview process, he asked many questions—most notably the common concern: “Do foreign companies lay off people easily?”

I explained our company culture as clearly as possible and encouraged him to join, emphasizing the opportunity to learn and work in a different environment. He accepted the offer.

Less than a year later, he resigned. His former manager had asked him to return, and he chose the familiarity of his previous company.

There was nothing inherently wrong with his decision. Trying is often necessary for growth—and regret tends to come from not trying at all. The real risk lies not in changing jobs, but in doing so without clarity about what you want to gain.

4. The Structural Advantage—and Constraint—of Being Foreign

Foreign professionals in Japan are not hired despite being foreign. They are hired because of it—when positioned correctly.

Common strengths include:

Global perspective

Cross-cultural communication

Experience working across systems

Specialized expertise (e.g., IT, finance, compliance, operations)

Strong risk awareness and adaptability, developed through navigating work and life in a foreign environment

At the same time, constraints remain:

Japanese language limitations

Visa scope restrictions

Misaligned expectations about autonomy or speed

Interestingly, as Japanese proficiency improves, many foreign professionals become more valuable, not less—because they combine local understanding with global context.

Real example:

Structural demand is particularly visible in compliance, risk management, internal control, and internal audit. In Japan, demand for these roles has continued to rise due to tighter corporate governance requirements, J-SOX internal control obligations, and alignment with global regulatory standards.

In one case, despite an extended search, we were unable to hire a mid-career full-time professional and ultimately hired a retired specialist on a part-time basis.

5. Timing Is About Risk, Not Speed

Job changes in Japan typically take 3 to 6 months from preparation to offer—longer if visa changes are involved. Waiting for a “perfect break” rarely works.

In Japan, hiring activity tends to increase:

February–March (new fiscal year): a good reason to begin preparing your job search now

August–September (second-half reinforcement)

These windows matter—but timing should be framed as risk management, not urgency. In a structurally constrained labor market, patience often leads to better alignment.

6. Retention Logic Has Changed—And You Should Adjust Accordingly

Lifetime employment and seniority still influence expectations, even as practices evolve.

From a hiring perspective:

Repeated short tenures raise concern (Typical job hoppers)

One sustained role (five years or more) can offset earlier movement

What matters is not the number of job changes, but whether someone has demonstrated the ability to stay, adapt, and contribute meaningfully.

This is especially true now. Hiring and training are expensive and time consuming.

7. Using Recruiters as Strategic Intermediaries

Recruitment agents focused on foreign professionals have expanded significantly in Japan, particularly at global firms.

That said, the individual agent matters far more than the firm. The difference between working with a capable agent and an average one can be night and day.

Look for an agent who:

Understands your long-term goals rather than pushing short-term placements

Communicates honestly about trade-offs and constraints

Responds reliably and follows through

Has firsthand experience working in Japan and understands its labor structure

Invests in a relationship you can carry forward

Recruiters should be treated as information partners, not decision-makers.

A brief note on AI and hiring in Japan

Talent acquisition is critical to business continuity, and recruiting costs already represent a substantial portion of HR budgets—particularly when hiring through expensive external agents. (This is one reason many companies increasingly favor referral hiring.)

At the same time, hiring decisions that rely heavily on career history or interview impressions can be highly subjective. In Japan, this tendency is reinforced by traditional practices such as requiring a photograph on resumes. Over the long term, AI has the potential to support more consistent and objective assessment, particularly in early-stage screening.

As AI adoption progresses, recruiters who fail to add meaningful value beyond screening will likely be displaced. In contrast, agents who can interpret context, articulate a candidate’s intent, and support long-term alignment will continue to play an important role.

8. Legal and Visa Awareness as Risk Control

Changing jobs in Japan is not only a career decision—it is also a risk-control exercise. Japanese labor law applies regardless of nationality, but visa status determines how much room you have to move.

Core labor law principles (high level)

Foreign employees in Japan are protected by the same labor laws as Japanese employees, including:

No discrimination based on nationality

Clear disclosure of working conditions

Restrictions on dismissal

Transparency around compensation and overtime

Mandatory enrollment in social insurance (health and pension)

Understanding these rights is necessary—but visa awareness determines whether you can act on them safely.

Visa mobility map (one-line overview)

Free mobility (no job-type restriction):

Permanent Resident (PR)/ Spouse of Japanese / Spouse of PR / Long-Term Resident

→ You can change jobs freely across industries.Conditional mobility (scope-restricted):

Engineer/Specialist in Humanities/International Services, Highly Skilled Professional, Manager, Intra-company Transferee, etc.

→ Job changes are possible, but role content must remain within visa scope, or permission/status change is required.

Common visa mistakes foreigners make

Assuming “job change” is always allowed

The issue is not the employer—it is whether the new role matches your visa category.Resigning first, checking visa later

Once unemployed, your risk tolerance drops sharply.Believing small role changes do not matter

Even subtle shifts in responsibilities can trigger a visa mismatch.Over-relying on informal advice

“My friend did it” is not a compliance strategy.

HR-view: dangerous job-change patterns

From an HR and risk perspective, the most problematic pattern is resigning without a secured next role.

Once unemployed, foreign workers are typically under intense pressure to find a new position within about three months, or face visa risk.

This pressure often leads to poor decisions, including accepting ill-fitting roles or unfavorable conditions.

Another common oversight is ignoring health insurance continuity. Gaps in coverage can create financial and administrative problems and may signal poor planning to employers. In many cases, employer-provided health insurance can be continued for up to two years after resignation under Japan’s voluntary continuation system, although premiums typically increase because the employer contribution ends.

Eligibility and timing should always be confirmed in advance. From a company’s perspective, candidates who manage transitions calmly and compliantly are seen as lower risk and more retainable.

👉 Related guide: Resignation in Japan: Legal Rights, Cultural Traps, and Expat Essentials

The takeaway

Visa constraints are not reasons to avoid mobility—they are reasons to plan carefully.

Confirm visa scope, insurance continuity, and legal conditions before resigning, not after.

In today’s labor market, informed planning is not caution—it is strategy.

9. The Psychological Traps to Avoid

Structural change often creates emotional pressure. Common traps include:

Holiday optimism (“Now is the time.”)

Pause and check: Would I make the same decision if I waited two or three weeks and reviewed it calmly?Panic switching, triggered by conflict or short-term frustration

Pause and check: Am I reacting to a temporary situation, or to a structural issue that will not improve?Visa-driven fear, leading to rushed decisions

Pause and check: Do I fully understand my visa options and timelines, or am I assuming the worst?Overconfidence in skill transfer, assuming past success will translate automatically

Pause and check: Have I verified how my skills are evaluated and used in the Japanese context?

A calm, informed approach consistently leads to better outcomes.

10.Q&A

Q1. Does age matter when changing jobs in Japan as a foreigner?

A1. Yes—but differently than many expect. While Japan traditionally favored younger hires, demographic pressure has shifted priorities. For mid-career professionals, clarity of role fit and retention potential now matter more than age itself, especially in corporate and specialist functions.

Q2. Is it better to change jobs while employed or after resigning?

A2. From an HR and risk-management perspective, resigning before you have a signed offer is strongly discouraged. Being unemployed sharply increases visa pressure, weakens negotiation leverage, and often creates negative signals for employers, suggesting urgency-driven decisions or resignation without a secured next role. Rent, utilities, and insurance payments continue regardless of employment status, adding financial pressure that often forces rushed decisions.

Interviews can be demanding to manage alongside work, but the risk of resigning without a signed offer is far higher. Until an offer is formally signed, nothing is guaranteed.

Q3. How do Japanese companies view salary negotiation for mid-career hires?

A3. Salary negotiation is acceptable—but only when handled carefully and at the right stage.

At foreign companies in Japan, compensation discussions are standard. HR or the hiring manager will typically ask about both current and desired salary during the interview process. This is the appropriate time to explain your expectations. Be aware that candidates are often required to submit a tax withholding slip (源泉徴収票) from their previous employer; discrepancies are easily detected.

At Japanese companies, negotiation is possible but carries more risk. Surveys indicate that roughly 33% of candidates attempt salary negotiation—and many of those succeed. Yet, employers also report that raising compensation at the wrong time or without proper justification may affect the hiring decision. In practice, raising compensation before mutual interest is established can reduce your chances.

Q4. Are internal transfers within the same company safer than external job changes?

A4. Often yes. Internal moves reduce visa risk, preserve benefits continuity, and signal retention intent. For foreigners, internal transfers can be a low-risk way to broaden scope without triggering compliance complexity.

Q5. How important is Japanese language ability for mid-career roles, really?

A5. It depends on the function, not the title. Even in global roles, internal communication, documentation, and decision-making often occur in Japanese. Incremental improvement can materially expand your options, even without full fluency.

Q6. Is it risky to move from a foreign company to a Japanese company mid-career?

A6. It can be—but also strategically valuable. Japanese companies may not always offer top-end compensation, but experience inside Japanese systems often adds long-term career capital, especially for governance, operations, and leadership roles.

Many large Japanese companies still tend to distinguish between employees hired as new graduates and developed internally over long tenures, and lateral hires. Understanding this structure helps set realistic expectations and make the move a deliberate investment rather than a short-term trade-off.

Q7. Should I prioritize company brand or role content?

A7. Role content almost always matters more long-term. Brand may help initially, but misaligned responsibilities are a leading cause of early exits, which are costly for both employee and employer.

Q8. What is the most overlooked factor in successful job changes in Japan?

A8. Decision timing combined with self-clarity. Most failed transitions are not due to skills gaps, but to unclear intent—moving too fast, or for the wrong reasons, in a system where reversal is costly.

11.Wrap-Up

Japan’s labor market is not simply aging. It is rebalancing.

Prime-age male employment is shrinking. Female participation is rising. Workplaces are adjusting—sometimes quietly, sometimes unevenly.

For mid-career foreign professionals, this does not promise easy wins or rapid salary growth. What it offers is something more durable: the chance to build career value in a system under real pressure to adapt.

The opportunity is not about moving fast.

It is about moving with intent—where structure, timing, and long-term value align.

If you’ve made a mid-career transition in Japan, your insights may help others—please consider sharing in the comments.

See also:

Can Your Employer Stop You from Switching Jobs in Japan? Non-Compete Rules Explained

Employment Contracts in Japan – What You Need to Know

Japan New Hire Checklist: From Pre-Arrival Paperwork to Your First 90 Days

Overtime in Japan: What’s Legal, What’s Not, and How to Protect Yourself